A bit of a profound question – triggered by a guest post on Museums Computer Group by Nick Poole CEO of The Collections Trust about Culture Grid and an overview of recent announcements about it.

A bit of a profound question – triggered by a guest post on Museums Computer Group by Nick Poole CEO of The Collections Trust about Culture Grid and an overview of recent announcements about it.

Broadly the changes are that:

- The Culture Grid closed to ‘new accessions’ (ie. new collections of metadata) on the 30th April

- The existing index and API will continue to operate in order to ensure legacy support

- Museums, galleries, libraries and archives wishing to contribute material to Europeana can still do so via the ‘dark aggregator’, which the Collections Trust will continue to fund

- Interested parties are invited to investigate using the Europeana Connection Kit to automate the batch-submission of records into Europeana

The reasons he gave for the ending of this aggregation service are enlightening for all engaged with or thinking about data aggregation in the library, museum, and archives sectors.

Throughout its history, the Culture Grid has been tough going. Looking back over the past 7 years, I think there are 3 primary and connected reasons for this:

- The value proposition for aggregation doesn’t stack up in terms that appeal to museums, libraries and archives. The investment of time and effort required to participate in platforms like the Culture Grid isn’t matched by an equal return on that investment in terms of profile, audience, visits or political benefit. Why would you spend 4 days tidying up your collections information so that you can give it to someone else to put on their website? Where’s the kudos, increased visitor numbers or financial return?

- Museum data (and to a lesser extent library and archive data) is non-standard, largely unstructured and dependent on complex relations. In the 7 years of running the Culture Grid, we have yet to find a single museum whose data conforms to its own published standard, with the result that every single data source has required a minimum of 3-5 days and frequently much longer to prepare for aggregation. This has been particularly salutary in that it comes after 17 years of the SPECTRUM standard providing, in theory at least, a rich common data standard for museums;

- Metadata is incidental. After many years of pump-priming applications which seek to make use of museum metadata it is increasingly clear that metadata is the salt and pepper on the table, not the main meal. It serves a variety of use cases, but none of them is ‘proper’ as a cultural experience in its own right. The most ‘real’ value proposition for metadata is in powering additional services like related search & context-rich browsing.

The first of these two issues represent a fundamental challenge for anyone aiming to promote aggregation. Countering them requires a huge upfront investment in user support and promotion, quality control, training and standards development.

The 3rd is the killer though – countering these investment challenges would be possible if doing so were to lead directly to rich end-user experiences. But they don’t. Instead, you have to spend a huge amount of time, effort and money to deliver something which the vast majority of users essentially regard as background texture.

As an old friend of mine would depressingly say – Makes you feel like packing up your tent and going home!

Interestingly earlier in the post Nick give us an insight into the purpose of Culture Grid:

.… we created the Culture Grid with the aim of opening up digital collections for discovery and use ….

That basic purpose is still very valid for both physical and digital collections of all types. The what [helping people find, discover, view and use cultural resources] is as valid as it has ever been. It is the how [aggregating metadata and building shared discovery interfaces and landing pages for it] that has been too difficult to justify continuing in Culture Grid’s case.

In my recent presentations to library audiences I have been asking a simple question “Why do we catalogue?” Sometimes immediately, sometimes after some embarrassed shuffling of feet, I inevitably get the answer “So we can find stuff!“. In libraries, archives, and museums helping people finding the stuff we have is core to what we do – all the other things we do are a little pointless if people can’t find, or even be aware of, what we have.

In my recent presentations to library audiences I have been asking a simple question “Why do we catalogue?” Sometimes immediately, sometimes after some embarrassed shuffling of feet, I inevitably get the answer “So we can find stuff!“. In libraries, archives, and museums helping people finding the stuff we have is core to what we do – all the other things we do are a little pointless if people can’t find, or even be aware of, what we have.

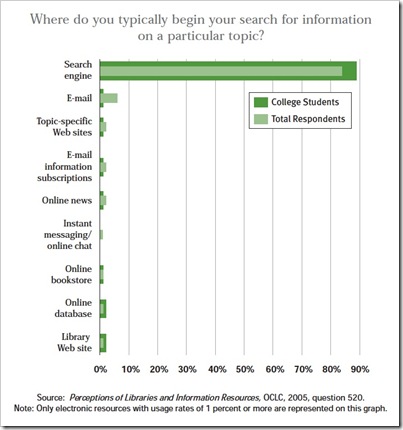

If you are hoping your resources will be found they have to be referenced where people are looking. Where are they looking?

It is exceedingly likely they are not looking in your aggregated discovery interface, or your local library, archive or museum interface either. Take a look at this chart  detailing the discovery starting point for college students and others. Starting in a search engine is up in the high eighty percents, with things like library web sites and other targeted sources only just making it over the 1% hurdle to get on the chart. We have known about this for some time – the chart comes from an OCLC Report ‘College Students’ Perceptions of Libraries and Information Resources‘ published in 2005. I would love to see a similar report from recent times, it would have to include elements such as Siri, Cortana, and other discovery tools built-in to our mobile devices which of course are powered by the search engines. Makes me wonder how few cultural heritage specific sources would actually make that 1% cut today.

detailing the discovery starting point for college students and others. Starting in a search engine is up in the high eighty percents, with things like library web sites and other targeted sources only just making it over the 1% hurdle to get on the chart. We have known about this for some time – the chart comes from an OCLC Report ‘College Students’ Perceptions of Libraries and Information Resources‘ published in 2005. I would love to see a similar report from recent times, it would have to include elements such as Siri, Cortana, and other discovery tools built-in to our mobile devices which of course are powered by the search engines. Makes me wonder how few cultural heritage specific sources would actually make that 1% cut today.

Our potential users are in the search engines in one way or another, however it is the vast majority case that our [cultural heritage] resources are not there for them to discover.

Culture Grid, I would suggest, is probably not the only organisation, with an ‘aggregate for discovery’ reason for their existence, that may be struggling to stay relevant, or even in existence.

You may well ask about OCLC, with it’s iconic WorldCat.org discovery interface. It is a bit simplistic say that it’s 320 million plus bibliographic records are in WorldCat only for people to search and discover through the worldcat.org user interface. Those records also underpin many of the services, such as cooperative cataloguing, record supply, inter library loan, and general library back office tasks, etc. that OCLC members and partners benefit from. Also for many years WorldCat has been at the heart of syndication partnerships supplying data to prominent organisations, including Google, that help them reference resources within WorldCat.org which in turn, via find in a library capability, lead to clicks onwards to individual libraries. [Declaration: OCLC is the company name on my current salary check] Nevertheless, even though WorldCat has a broad spectrum of objectives, it is not totally immune from the influences that are troubling the likes of Culture Graph. In fact they are one of the web trends that have been driving the Linked Data and Schema.org efforts from the WorldCat team, but more of that later.

You may well ask about OCLC, with it’s iconic WorldCat.org discovery interface. It is a bit simplistic say that it’s 320 million plus bibliographic records are in WorldCat only for people to search and discover through the worldcat.org user interface. Those records also underpin many of the services, such as cooperative cataloguing, record supply, inter library loan, and general library back office tasks, etc. that OCLC members and partners benefit from. Also for many years WorldCat has been at the heart of syndication partnerships supplying data to prominent organisations, including Google, that help them reference resources within WorldCat.org which in turn, via find in a library capability, lead to clicks onwards to individual libraries. [Declaration: OCLC is the company name on my current salary check] Nevertheless, even though WorldCat has a broad spectrum of objectives, it is not totally immune from the influences that are troubling the likes of Culture Graph. In fact they are one of the web trends that have been driving the Linked Data and Schema.org efforts from the WorldCat team, but more of that later.

How do we get our resources visible in the search engines then? By telling the search engines what we [individual organisations] have. We do that by sharing a relevant view of our metadata about our resources, not necessarily all of it, in a form that the search engines can easily consume. Basically this means sharing data embeded in your web pages, marked up using the Schema.org vocabulary. To see how this works, we need look no further than the rest of the web – commerce, news, entertainment etc. There are already millions of organisations, measured by domains, that share structured data in their web pages using the Schema.org vocabulary with the search engines. This data is being used to direct users with more confidence directly to a site, and is contributing to the global web of data.

There used to be a time that people complained in the commercial world of always ending up being directed to shopping [aggregation] sites instead of directly to where they could buy the TV or washing machine they were looking for. Today you are far more likely to be given some options in the search engine that link you directly to the retailer. I believe is symptomatic of the disintermediation of the aggregators by individual syndication of metadata from those retailers.

Can these lessons be carried through to the cultural heritage sector – of course they can. This is where there might be a bit of light at the end of the tunnel for those behind the aggregations such as Culture Grid. Not for the continuation as an aggregation/discovery site, but as a facilitator for the individual contributors. This stuff, when you first get into it, is not simple and many organisations do not have the time and resources to understand how to share Schema.org data about their resources with the web. The technology itself is comparatively simple, in web terms, it is the transition and implementation that many may need help with.

Schema.org is not the perfect solution to describing resources, it is not designed to be. It is there to describe them sufficiently to be found on the web. Nevertheless it is also being evolved by community groups to enhance it capabilities. Through my work with the Schema Bib Extend W3C Community Group, enhancements to Schema.org to enable better description of bibliographic resources, have been successfully proposed and adopted. This work is continuing towards a bibliographic extension – bib.schema.org. There is obvious potential for other communities to help evolve and extend Schema to better represent their particular resources – archives for example. I would be happy to talk with others who want insights into how they may do this for their benefit.

Schema.org is not the perfect solution to describing resources, it is not designed to be. It is there to describe them sufficiently to be found on the web. Nevertheless it is also being evolved by community groups to enhance it capabilities. Through my work with the Schema Bib Extend W3C Community Group, enhancements to Schema.org to enable better description of bibliographic resources, have been successfully proposed and adopted. This work is continuing towards a bibliographic extension – bib.schema.org. There is obvious potential for other communities to help evolve and extend Schema to better represent their particular resources – archives for example. I would be happy to talk with others who want insights into how they may do this for their benefit.

Schema.org is not a replacement for our rich common data standards such as MARC for libraries, and SPECTRUM for museums as Nick describes. Those serve purposes beyond sharing information with the wider world, and should be continued to be used for those purposes whilst relevant. However we can not expect the rest of the world to get its head around our internal vocabularies and formats in order to point people at our resources. It needs to be a compromise. We can continue to use what is relevant in our own sectors whilst sharing Schema.org data so that our resources can be discovered and then explored further.

So to return to the question I posed – Is There Still a Case for Cultural Heritage Data Aggregation? – If the aggregation is purely for the purpose of supporting discovery, I think the answer is a simple no. If it has broader purpose, such as for WorldCat, it is not as clear cut.

I do believe nevertheless that many of the people behind the aggregations are in the ideal place to help facilitate the eventual goal of making cultural heritage resources easily discoverable. With some creative thinking, adoption of ‘web’ techniques, technologies and approaches to provide facilitation services, reviewing what their real goals are [which may not include running a search interface]. I believe we are moving into an era where shared authoritative sources of easily consumable data could make our resources more visible than we previously could have hoped.

I do believe nevertheless that many of the people behind the aggregations are in the ideal place to help facilitate the eventual goal of making cultural heritage resources easily discoverable. With some creative thinking, adoption of ‘web’ techniques, technologies and approaches to provide facilitation services, reviewing what their real goals are [which may not include running a search interface]. I believe we are moving into an era where shared authoritative sources of easily consumable data could make our resources more visible than we previously could have hoped.

Are there any black clouds on this hopeful horizon? Yes there is one. In the shape of traditional cultural heritage technology conservatism. The tendency to assume that our vocabulary or ontology is the only way to describe our resources, coupled with a reticence to be seen to engage with the commercial discovery world, could still hold back the potential.

As an individual library, archive, or museum scratching your head about how to get your resources visible in Google and not having the in-house ability to react; try talking within the communities around and behind the aggregation services you already know. They all should be learning and a problem shared is more easily solved. None of this is rocket science, but trying something new is often better as a group.

RT @DataLiberate: Is There Still a Case for Aggregations of Cultural Data: A bit of a profound question http://t.co/jYHrXrpkJQ

I find the most compelling motivation for aggregation of cultural heritage resources is when that process creates a platform that allows the collections to be used in new ways. The APIs provided by DPLA and Europeana, for example, make it much easier for small institutions to have their data available via an API. It also makes it much easier for those who want to use the collections in novel ways to do so, and to use much larger sets of data, rather than learning everyone’s local API schema.

Is There Still a Case for Aggregations of Cultural Data, ask @rjw and @NickPoole1 http://t.co/zcSK14Bk4B

Is There Still a Case for Aggregations of Cultural Data? http://t.co/Tg7O2JQwXO

Is There Still a Case for Aggregations of Cultural Data | Data Liberate http://t.co/bwVHxSMcoR, see more http://t.co/1IqoMON3XW

Is There Still a Case for Aggregations of Cultural Data | Data Liberate http://t.co/WD41ispirB, see more http://t.co/dLmEwYXOkw

RT @DataLiberate: Is There Still a Case for Aggregations of Cultural Data: A bit of a profound question http://t.co/jYHrXrpkJQ

RT @DataLiberate: Is There Still a Case for Aggregations of Cultural Data: A bit of a profound question http://t.co/jYHrXrpkJQ